|

|

Makerbot Industries – Replicator 2 – 3D-printer 11 | Flickr – Photo Sharing!

Creative Tools Attribution 2.0 Generic | CC BY 2.0 |

The 3D printer is presently a hobbyist’s tool, one fostering a society of makers who have found a useful medium with which to let their imaginations run loose. 3DP business have sprung out with specialties in art, décor, fashion, and novelty. Beyond that, however, 3DP has yet to achieve an appreciable breakthrough—a killer app to transform the printer from an interesting gadget to an essential household appliance.

Given this fact, one ponders the 3D printer’s trajectory. Where will that trajectory lead? When will it get there? For that answer, one should look at the early years of the home computer.

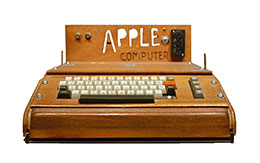

The home computer, after all, spent its first decade largely in the hands of the hobbyist because of its complexity and cost. Aside from the wealthy, only the electronics enthusiast had the willingness to spend and learn how to use the early home computer. Micro-Instrumentation Telemetry Systems’ (MITS) Altair 8800 retailed for $650 in 1975 (equal to about $2,800 in 2014), Processor Technology’s Sol Terminal Computer retailed for $2,100 in 1976 ($8,700 today), and the Apple 2 retailed for $1,300 in 1977 ($5,000). The need for a buyer to supply his own keyboard and monitor added to the cost, while the need to understand a programming language (usually Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, or BASIC) further hindered the personal computer’s accessibility to the general public.

Despite its limitations, the early PC fostered commercial, cultural, and technical innovation. Local clubs were set up in which members showcased discoveries, exchanged solutions, and conjured up new ideas. Northern California’s Homebrew Computer Club is the best remembered of these early outfits, having been a staging ground for the likes of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Sid Meier and Will Wright, pioneering designers of PC games, both started their careers by programming computer software at home.

Then there is the hacker, whose culture found formed seeking novel (though not always ethical) uses for the PC. The hacker community has become the most enduring of these early enthusiasts, finding new opportunity in every step of the computer’s evolution. The hacker’s place and purpose were best articulated by Loyd Blankenship, author of the so-called The Hacker Manifesto. The essay, published in 1986, explained the rationale behind and justification for hacking. Despite Blankenship’s ethos, the hacker’s knowledge has often been put to criminal use, attacking governments, businesses, and consumers. Such is the struggle that knowledge and technology bring.

There is an underlying philosophy underpinning the hobbyist/consumer dynamic. The hobbyist greets heightened challenge and complex processes as part of an enjoyable experience, while the consumer wants to avoid them. The consumer sees complexity as a burden to completing a task, whether it’s checking out news on the Web or printing a report for school. The consumer simply wants his device ready out-of-the-box and with the fewest steps possible to operate.

So we get to 3D printing.

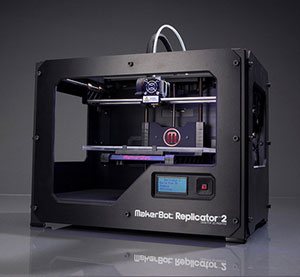

The consumer 3D printer is in its youth, experiencing the same two factors that steered the early PC towards the hobbyist: complexity and cost. The early PC required one’s knowledge in programming, while the 3D printer often requires a user’s knowledge in Computer-Aided Design (CAD) in order to generate and print objects. The average cost of a 3DP is, like those early PCs, relatively high, hovering around $1,500. (It should be pointed out that this is still minor compared to the adjusted cost of early PCs.) Many 3DPs, like old PCs, are sold as kits—something hobbyists love and typical consumers loathe…

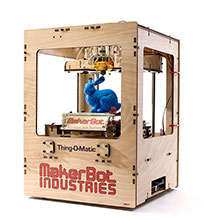

Then there are the visual parallels:

|

|

| By Makerbot Industries [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

By Ed Uthman (originally posted to Flickr as Apple I Computer) [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

Design: The MakerBot Thing-o-Matic, the first serious 3D printer on the consumer market, featured a bare, wooden exterior, one that evokes the Apple 1 in its utilitarian aesthetic. The emphasis in both is function-over-form: The device can be just plain ugly, but that doesn’t mean a lot as long as its does its intended function.

|

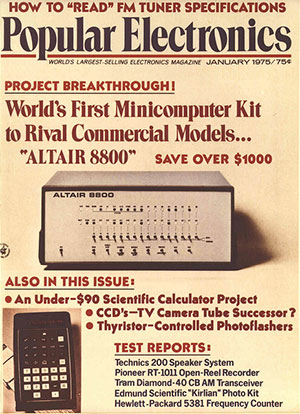

Media: Major publications have spotlighted particular hardware as being emblematic of an impending revolution. Popular Electronics featured the Altair 8800 on its January 1975 cover, proclaiming the machine to be the “world’s first minicomputer kit.” Fast-forward thirty-five years to see the MakerBot Cupcake on the cover of Make Magazine with the headline: “Your Desktop Factory.” Both are examples of impassioned rhetoric.

|

|

Time – Commemorative Issue Steve Jobs | Flickr – Photo Sharing!

Playing Futures: Applied Nomadology Attribution 2.0 Generic | CC BY 2.0 |

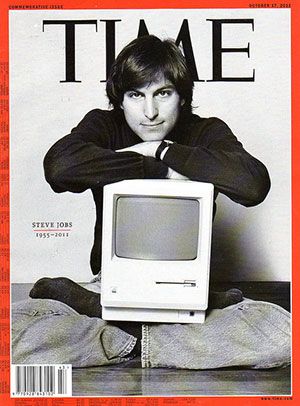

Icons: The public is drawn to human symbols. Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple, came to be associated with the computer’s breakthrough into the mainstream with the Macintosh. Have a look at the iconography surrounding MakerBot co-founder Bre Pettis and his Replicator 2. See any similarities?

3DP even has its own breed of innovator, its own hacker, in the form of the maker. Mark Hatch, founder of TechShop, authored The Maker Movement Manifesto, arguably an equivalent to Blankenship’s manifesto (or at least an homage) in 2013. Hatch’s publication is emblematic of the maker’s growing presence in what could be affectionately termed as “Geekdom.” Makers have started up businesses (Shapeways), ignited memes (Sad Keanu), organized

collective sharing grounds, and garnered widespread news coverage. They, like hackers, are spearheading cultural and technical innovation.

Every revolution takes time. The home computer made incremental steps toward mainstream acceptance and common use. Exterior design became more appealing, user interface more graphical, and memory storage larger. Those improvements converged so that, by the mid-1990s, the personal computer became as common in the home as a stove or washer.

Hype, skepticism, and impatience will continue to accompany the 3D printer’s rise. Make no bones about it: That rise will continue. There’s already been a precedent.